Jerry Girley joined the Navy in 1979. His service to the country led him to Orlando, where he was stationed at the Naval Training Center in Orlando’s Baldwin Park neighborhood. He married a hometown girl, Phyllis, in 1980 an they bought their first home in 1986.

Two children later, they had outgrown that home, and started their search for a new place to raise their family. That was in 1994. Decades prior, they wouldn’t have even been allowed in the city after sundown.

Girley, being a California native, was enticed by the house, its cost and the community.

His wife, who grew up in Apopka, had heard stories about Ocoee, and what Blacks referred to as a sundown town. “First thing she said is ‘Black people cannot, are not permitted to live in Ocoee,’ which coming from Southern California it’s like, ‘What are you talking about?” Jerry Girley said. “’This is the 20th Century. This is 1996. What do you mean Black people can’t live in Ocoee? It’s not computing.”

Phyllis Girley had heard horror stories about living in Ocoee if you were Black.

“My grandparents lived in Apopka, and my grandfather would also alert me about, well, Ocoee, you can’t go anywhere near Ocoee. You can’t drive by, you certainly can’t be there after dark …you could be hung and you could be killed, it was really like something out of the movies, the way he described it to me,” Phyllis Girley recalled.

After Reconstruction

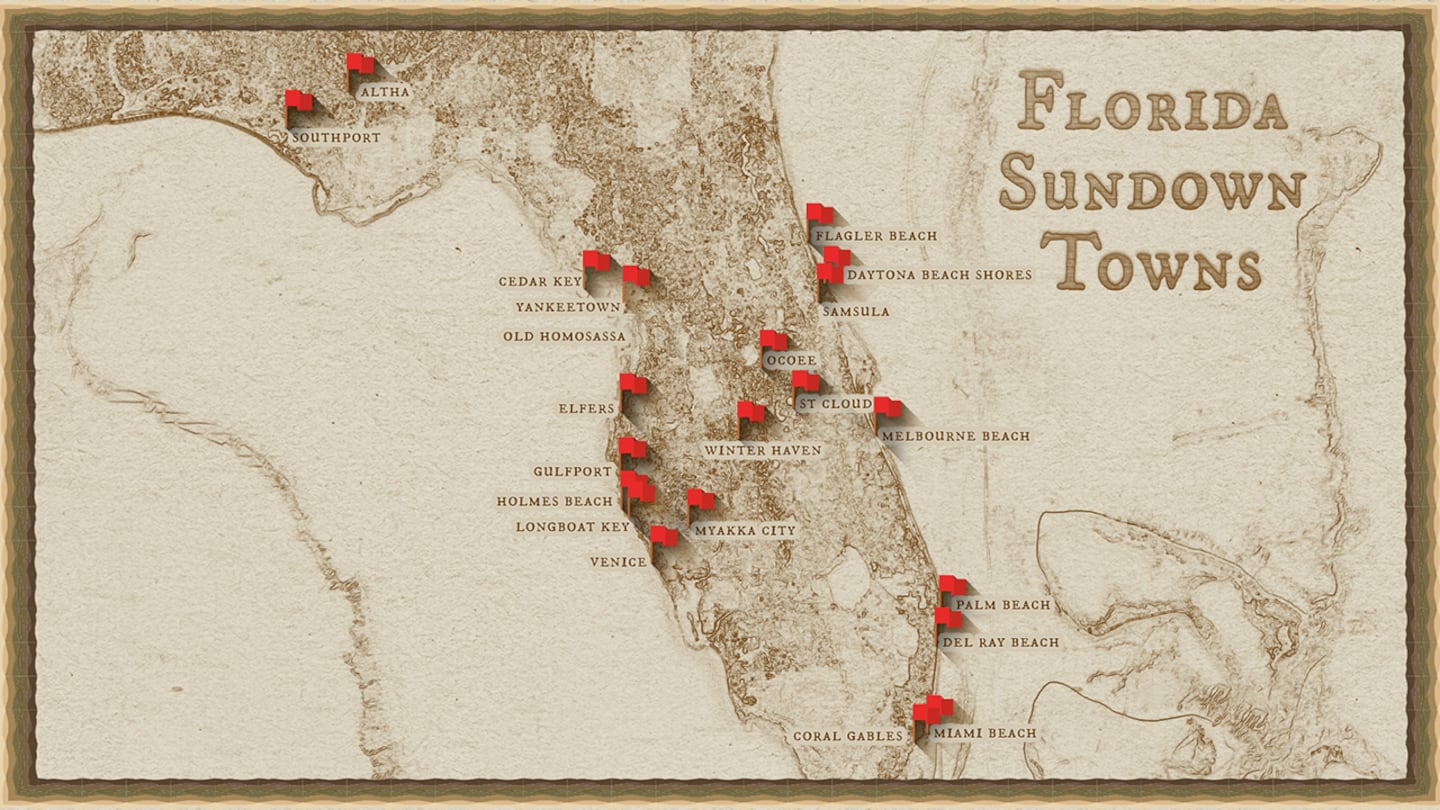

Decades ago, after the end of Reconstruction, towns and counties across the country became so called, “sundown towns.” These were all white communities that intentionally kept Blacks out of town, by force, law or custom. Some even posted signs warning, “*egro” Don’t Let The Sun Go Down on You" or “We Want White Tenants In Our Community.” Blacks knew that to mean they could face violence or even death if they were caught in town after dark.

“Often, people of different backgrounds or ethnicities could work or be there to help stimulate the economy, but could not remain there after sunset,” said Pam Schwartz, chief curator of the Orange County Regional History Center, which produced an exhibit detailing what led up to the Ocoee Massacre and what followed. “Especially after dark is when most crime happens. White people thought by keeping these individuals out, the community would be safer. That was the white people’s beliefs.”

Sometime after the 1920 Ocoee Massacre, the bloodiest day in modern American political history, Ocoee became a sundown town. After the massacre, Blacks were forced out of Ocoee. Their homes, schools and churches were burned by an angry white mob, upset that Black residents had tried to vote in the presidential election. But they also wanted their land.

"There are no definitive years for when Ocoee’s status as a sundown town began and ended. “I believe it happens differently for each town. Some gradually, some abruptly after instances of violence,” Schwartz said. “In the case of some communities, a sign is posted making the community’s wishes clear. In the case of Ocoee, it was as likely that Black people just didn’t want to go there, as much as white people didn’t want them to come. It was clearly unsafe for them to do so,” Schwartz said.

“There was no diversity in this city.”

— Mayor Rusty Johnson, Ocoee

The Census Data

According to census data, no Black people lived in Ocoee in 1950 and 1960 as compared to the 1,370 and 2,628 white people who were reported living there, respectively. The first known Black family moved back to Ocoee in the mid-70s. And now the city boasts a population of about 10,000 Black residents, which represents about 19 percent of the population.

Ocoee Mayor Rusty Johnson recounts moving to the city when he was just 9-years-old and growing up around people who only looked like him. “There was no diversity in this city. No, I went to high school with all, all of us were Caucasians, no diversity. I worked at the Winn-Dixie, I worked on jobs for my father where there was you know, contractors.”

By 1990, 168 Black people and 12,778 white people were reported living in Ocoee, census data shows. Phyllis Girley recalls how the diversity over the years in Ocoee gave her some comfort. “When we first go there, I think it was maybe two Black families that I remember being there, which gave me some comfort because they were already there,” she said. “I didn’t really go out and mingle with too many people because I was still a little nervous being in Ocoee, particularly about my kids and how they would be treated. My cousin moved in one street over within the year after we moved in, so that gave me comfort as well.”

For some, the history of Ocoee and its reputation as once being a Sundown Town has long-lasting implications.

Francina Boykin was pulled over in Ocoee one night in 1981.

“Everything just collapsed inside of me,” Boykin said. “I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, this is it.’ For me, everything came back to all the fears we were told. We just figured because nobody lived here at the time but white people that we shouldn’t be in Ocoee after sundown.”

In 2018, the city issued a proclamation acknowledging the massacre and in it, wrote: “Let it be known that Ocoee shall no longer be the sundown city but the sunrise city, with the bright light of harmony, justice, and prosperity shining upon all our citizens.”

Day of Remembrance Proclamation of 1920 by WFTV on Scribd

Cox Media Group