The Southern Baptist and Northern Methodist Quarters burned through the night. Those still living only spoke of it in whispers. Whispers of the mob that formed, the residents who died, some say burned alive, and the land and wealth lost. Whispers to every Black person nearby that “whatever you do, do not go to Ocoee.” A refrain repeated so many times, by so many generations, that over decades, the whisper grew to a roar.

The Fear

“I started telling people,” said Pauline James. “And everybody was trying to talk me out of it.” James was alone in her excitement about the home she planned to build. She would finally own a piece of land, and a home. She secured the land through Homes in Partnership, a program then and now financed by the United States Department of Agriculture. James and other low to moderate-income families received a direct loan to achieve home ownership.

It was homeownership, not making history, that was on James' mind when she purchased the parcel of land in an Ocoee neighborhood in 1976. She was a single mother, looking for a place to raise her family. She was on the hunt for a safe place where she and her six children could live under one roof. And she thought she had found that haven in Ocoee. “Everybody was trying to talk me out of it,” she said, recounting conversations with family and friends. “'You know what had happened?'” James remembers them asking. “I’d never even heard what had happened.”

The Exodus

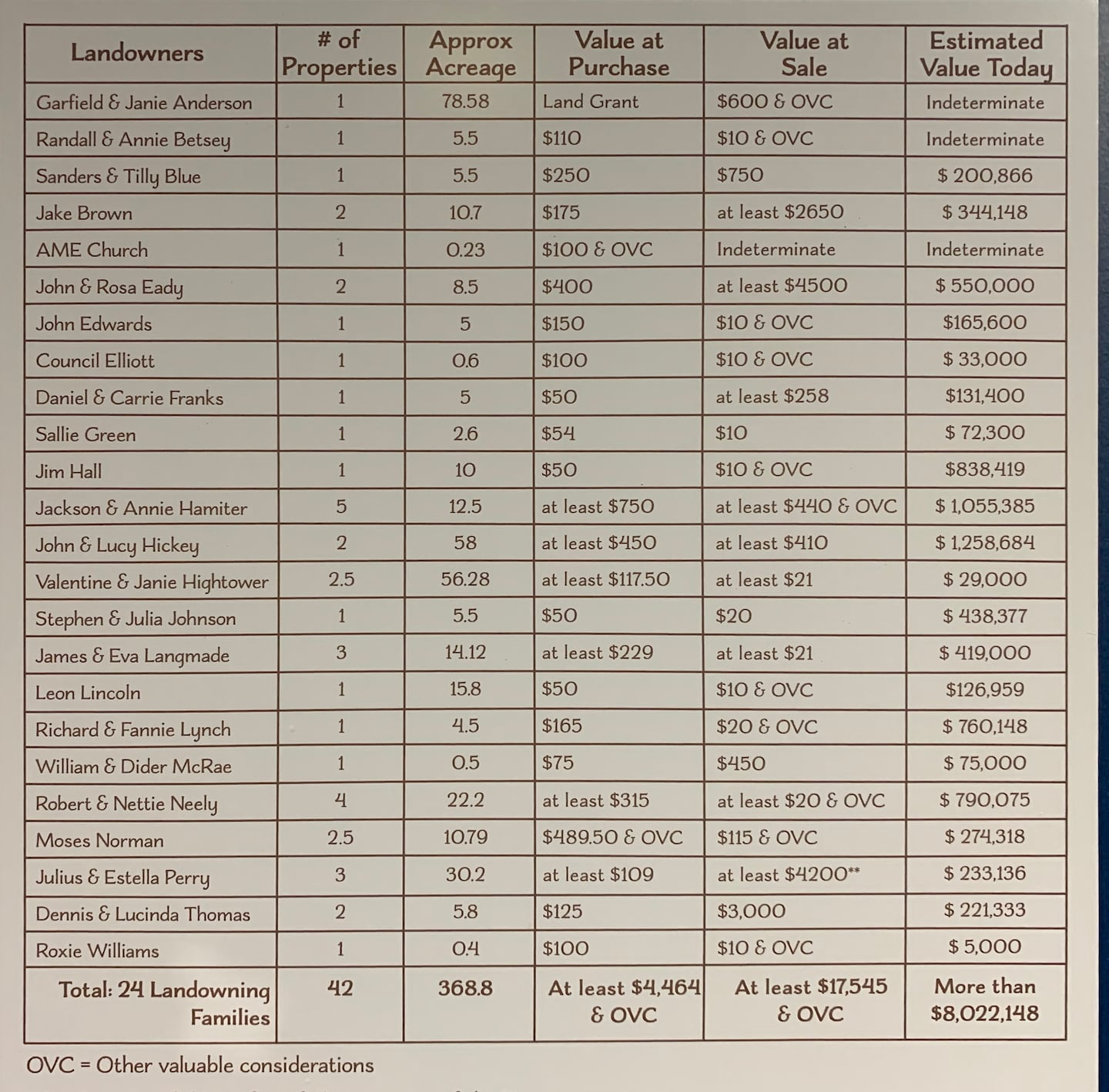

According to accounts in four Florida newspapers, at least 20 to 25 houses were burned down in the days following the Nov. 2 Ocoee Massacre. Two churches, a Black lodge and school were also burned. The headline on the local paper the next morning ignored the destruction of the black communities, and stated boldly, ‘Two Whites Dead In Ocoee Riot.’ An untold number of Blacks were killed. Accounts vary from a few up to 60, and there is no dispute that Julius ‘July’ Perry was lynched.

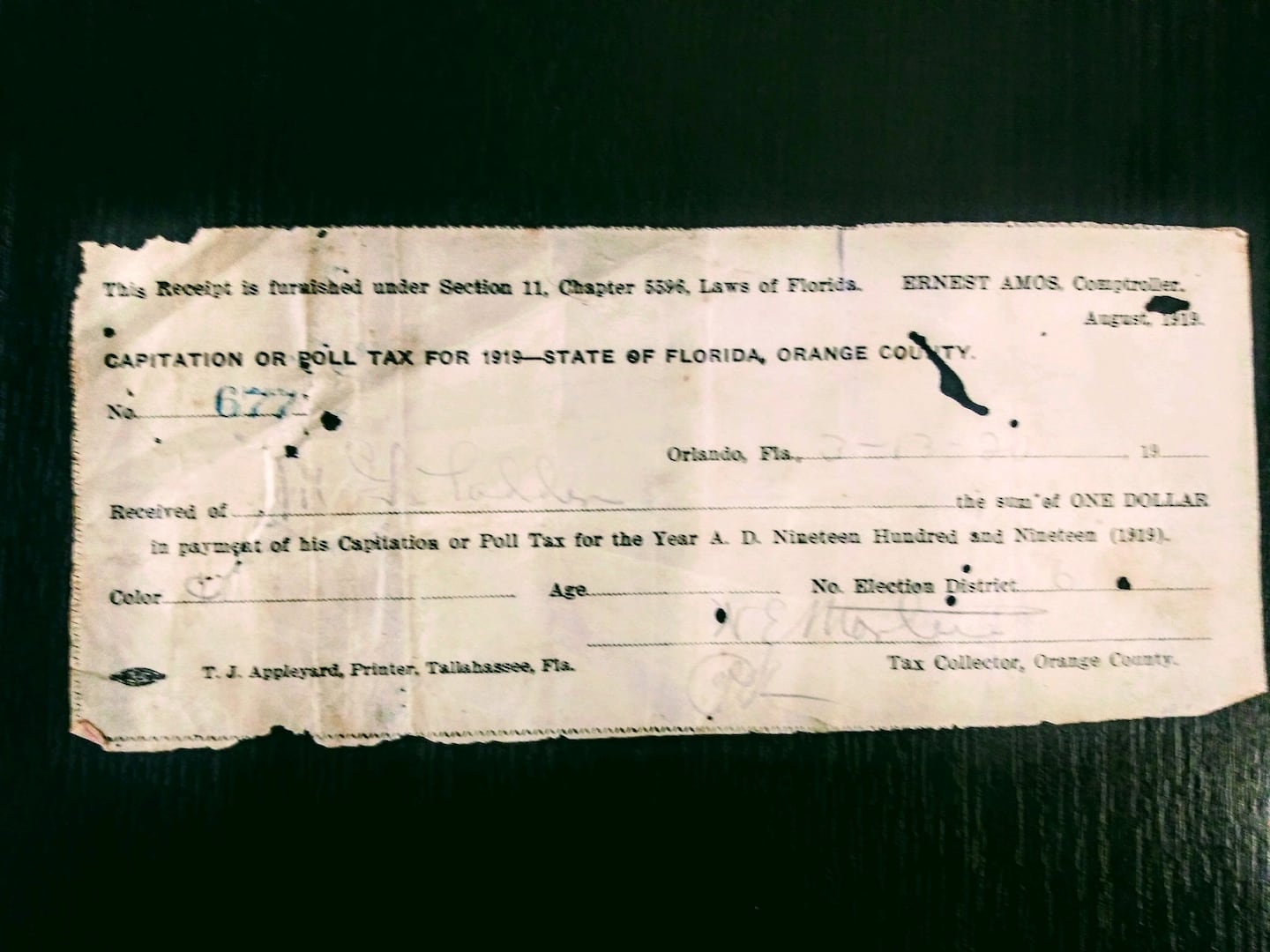

Perry and another prosperous farmer, Moses Norman, had rallied Blacks in their community and encouraged them to vote in the election. When election day arrived, Norman was refused at the polling site. A group of whites stopped him. They claimed he hadn’t paid his poll tax; the fee was required to discourage Blacks from voting.

Norman first went to the home of Judge John Cheney, who had helped him, and Perry organize voter registration drives for Blacks. Cheney encouraged him to return to the polling site to try to vote. Norman did, and he was refused again. Norman then went to Perry’s home. By then, angry whites were organizing a mob to go look for Norman.

Within hours, many of the 255 Black residents had no homes to return to. According to the 1920 census, 255 residents were divided among 82 households; some families as large as 10 or 13 people. With up 25 homes burned to the ground, that meant as many as a third of all Black residents' homes had gone up in smoke. Ashes were all that remained of the extraordinary achievement of home ownership in the Deep South less than 60 years after some of the residents had been freed from slavery.

Much of the growing middle-class Black community was gone. Afraid of what might follow such destruction, the Florida Times Union reported 15-year-old Chester Plummer, “a small Negro boy”, hid under a store without food and water for 48 hours. Many of his neighbors, they reported, were seen walking away from Ocoee, but not leaving by train. While many of the newspaper accounts about what happened on election night were conflicting, Census records confirm the Blacks had vanished.

Those who managed to escape the violence went all over. Some left for nearby Plymouth, Apopka, or other Florida cities. Others decided to leave Florida entirely, packing for other states.

“The Klansmens will be shooting anything.”

— Gladys Franks Bell

Gladys Franks Bell wrote about her family’s escape in her book, ‘Vision Through My Father’s Eyes.’ Bell’s family had relatives in Plymouth, so that is where they went.

“Word had gotten around, so my grandad, and I imagine some of the others had made a plan. They had to make a plan, escape plan and plan how they were going to connect up with the others,” Bell said. “They knew that if he could get his children and them [to] Plymouth, they [would] be safe and welcome.”

Bell said her father was only 18-years-old at the time and lived in the home with his six siblings: three girls and three boys. “I get emotional about it because they had to run. And my dad, one of the brothers was a paraplegic, so they had to, my dad had to carry him on his back and hold the others hand in hand. And they had to run sometime. They were able to walk. They had to go into the swampy area, out [a]round Lake Apopka. And, my dad said … his dad had told him, stay in the bushes, stay out of sight because the Klansmens will be shooting anything,” Franks Bell recalled.

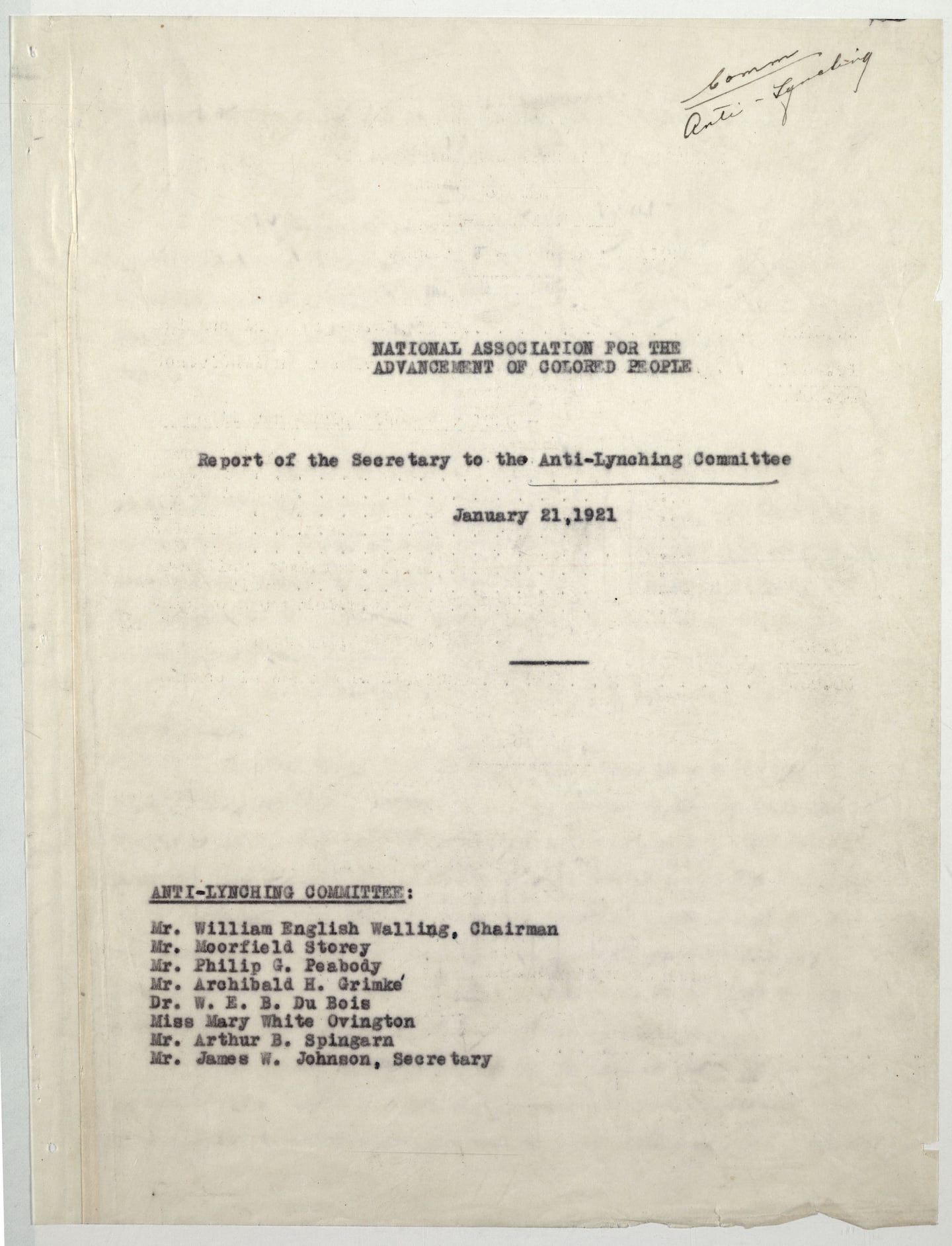

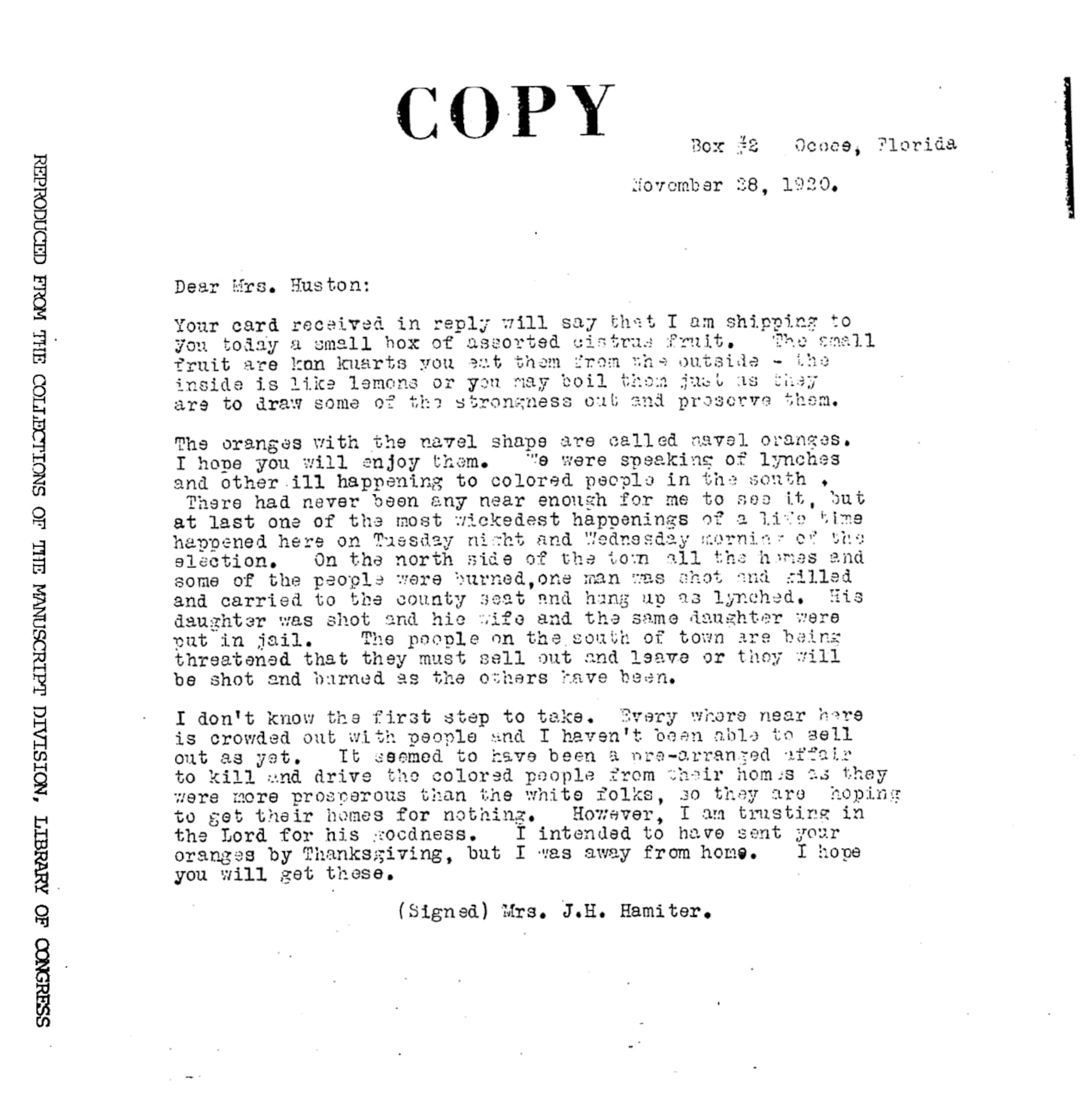

One Ocoee resident, known as J.H. Hamiter, included a letter in an orange shipment. The letter provided an account of what happend to the recipient; its information was included in an NAACP report. The beginning of the letter reads as though Hamiter is describing fruit, but she goes on to detail what happened on Nov. 2-3, 1920.

“At last one of the most wickedest happening of a life time happened here on Tuesday night and Wednesday morning of the election,” she wrote. “On the north side of the town all the homes and some of the people were burned, one man was shot and killed and carried to the county seat and hung up as lynched. His daughter was shot and his wife and the same daughter were put in jail. The people on the south of town are being threated that they must sell out and leave of they will be shot and burned as the others have been,” Hamiter wrote. “It seemed to be a pre-arranged affair to kill and drive the colored people from their homes as they were more prosperous than the white folks, so they are hoping to get their homes for nothing. However, I am trusting in the Lord for goodness,” Hamiter wrote.

Special Bargains

Within two weeks, advertisements printed in Orlando and Miami newspapers offered the sale of groves and grove land in Ocoee as “special bargains.” One advertisement published six weeks later on December 12th read, “several beautiful little groves belonging to the *egroes that have just left Ocoee. Must be sold – see B.M. Sims, Ocoee, FLA.”

By the time the 1930 Census rolled around, the number of residents listed under “*egroes" had fallen from 255 people to just two. Former Ocoee Mayor and Orange County high school principal Lester Dabbs wrote in his published 1969 thesis that one of those residents was Burly Jones, a former slave. One of three Blacks in Ocoee born before the end of the Civil War, he was too sick to leave.

For the 1940 Census, there are six people listed under “*egro”, but none of them are there ten years later. Instead, the 1950 Census shows dashes under “*egro”. Those official records show not a single Black person was left in the city. The dashes persisted until the 1980 Census, three years after Pauline James and her family moved into their home.

“I also had one of my teachers tell me that we were the first Black students that he ever had.”

— Marcy Bodiford

The First

“We would just be driving down the street and they will be calling us all kinds of n***ers and other,” said James.

That was the welcome Pauline James and her family received. “I told them, don’t say nothing. Just ignore him.” Harder to ignore were the bottles James and her daughter, Marcy Bodiford, said were thrown through their windows in the middle of a cold night. “By the grace of God, we never woke up,” Bodiford said. “If we would have, we would have been scared to death to be woke up out of your sleep with bottles being thrown in your windows.”

They had just moved in.

“My kids, they had way more trouble than I did,” said James. “They suffered way more than I did.” Bodiford was in the first grade when her family moved into the four-bedroom, one-bathroom house in Ocoee her mother still calls home today. Other Black families, they say, began moving in around the same time. And this time, some of them stayed, unlike the Black families said to have been run out of town before they even got settled. And nobody besides Pauline James was brave enough to enroll their kids into the local schools.

“They didn’t send their kids to [Ocoee] schools,” said James. “They took them to Apopka because we already knew it was dangerous.” Black parents at the time also enrolled their kids in Winter Garden, James and Bodiford said. Both cities had much larger Black populations.

Bodiford’s earliest memories of school in Ocoee are full of slurs regularly hurled at her and her siblings. Racist classmates provoked fights and tried to humiliate them. “I had older kids that would taunt me, take their books and rub it on my head and say, ‘Oh my gosh, look at all the grease in your hair,’” said Bodiford.

But she also had classmates she feels grew up to be different than they might have if they hadn’t met her. If not for her family, she knows some wouldn’t have spent any significant time with Black children until they were nearly grown. “I also had one of my teachers tell me that we were the first Black students that he ever had,” Bodiford said. “And you know, he said he learned a lot from us.”

And Bodiford’s neighborhood she says, was its own education; a growing tapestry of diversity. “The street that I grew up on, it was amazing during that time,” she said. “We had a Spanish-speaking family that was Puerto Rican. We had two families from Guyana. We had neighbors that the wife was from Vietnam.”

A street that was one sign of the change coming to Ocoee.

The Familes That Followed

The change was small at first— a whisper.

In the late 70s and early 80s, Bodiford’s best friends were some of the kids on her street, both white and non-white. “As kids, they got to know us, so they liked us for who we were and they really weren’t exposed to racism,” she said. “So, it was just mainly the people that lived in Ocoee and grew up in Ocoee that had a lot of racist attitudes or whatever.”

But the path to a more diverse city was a zig zag—at times moving toward progress, then pulling back, as if magnetized, toward the dynamics that kept Ocoee all white for decades. Between 1980 and 1990, Ocoee’s growth exploded, nearly doubling from its population of 7,803 residents. But as the city grew, in that decade it also grew whiter. By 1990, the city’s miniscule Black population of 0.4 percent was down to 0.1 percent.

And then, a spark.

Exactly 20 years after Pauline James and her children broke barriers in Ocoee, Tonja Sparks and her family moved to the city.

So much had changed.

The city was three times bigger. Families of all races, ethnicities and religions were flocking to the community west of Orlando—west of where housing and construction prices had ballooned. And yet, Tonja Sparks would discover unease, discomfort—it was all still there, just below the surface.

In her family’s neighborhood of about 50 households, she recalled only three of the families living there were Black when they moved in. “The neighbors on either side of us on both sides, they moved first and then the neighbor across the street moved,” said Sparks. In her settled neighborhood full of retirees and long-time families, it struck her as strange. “For sale signs started going up,” Sparks said. “Then I realized that there’s something going on here.”

She remembered another time shortly after her arrival when she called a friend, confused about the abundance of stares she received inside an Ocoee Walmart. Her friend, she said, told her that’s simply what she should expect as a Black person living in Ocoee. Quickly, she realized other Black parents and families had to all figure out how to exist in a city with such a violent history targeting the Black community. A city they felt had remained insulated from some of the changing attitudes in America, by virtue of Black Floridians' fear of even driving through it. “We lived in Ocoee, but we didn’t necessarily shop in Ocoee, go to school in Ocoee,” said Sparks. “We just were residents of Ocoee.”

Just one year before, Jerry Girley had learned how deep the fear ran among Black people like his wife Phyllis, who had grown up in nearby Apopka. He had had found a home with a design he liked in another part of West Orange County and was giddy at the prospect of getting the same exact home for $50,000 less in Ocoee. “I’m excited and I run home and I say, ‘Honey, guess what? I found our house. It’s in Ocoee. We’re going to move to Ocoee,’” Girley said. “And she looked at me without batting an eyelash and said, ‘No, we’re not.’”

Like most, Phyllis wasn’t taught the specifics of what happened in Ocoee on Election Day 1920. But she knew enough that she didn’t want to live there. Jerry, over time, was able to convince her. But her fear stuck with him. Her concerns were so great she left her job at Florida Hospital, took a job at her children’s school and stuck to herself. “I didn’t really go out and mingle with too many people. Because I was still a little bit nervous being in Ocoee particularly about my kids and how they would be treated,” she said.

Though the scar tissue is still there, twenty more years on, Ocoee is practically unrecognizable from the outside. According to the 2018 Census, Black residents now make up about 19.5% of Ocoee’s population of 35,292. It’s a far cry from the all-white city of a few thousand that Pauline James moved her family to in 1977.

No Regrets

But despite their challenges, James and her daughter say they have no regrets about starting the return of Black residents to Ocoee. “I credit her for being bold enough to do something that a lot of people weren’t willing to do,” said Bodiford of her mom. “Move in a place where people had been ran out, where Black people could not be after sundown.”

And she believes the racial makeup of the city today is proof that no matter the remaining challenges, their struggles were not entirely in vain. “I felt like we paved the way to make a change in Ocoee so that Black people would be more accepted.”

Cox Media Group